How Do Rulers Use Art and Architecture to Legitimize Their Rule

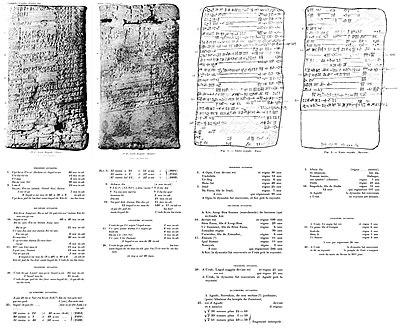

The Sumerian King Listing inscribed onto the Weld-Blundell Prism, with transcription. | |

| Original title | 𒉆𒈗 (Nam-Lugal "Kingship").[1] |

|---|---|

| Translator |

|

| State | Sumer (ancient Iraq) |

| Language | Sumerian |

| Subject | Regnal listing |

| Genre | Literary |

| Set in | Late-third to early-second millennia BC |

| Publication date | Ur Three to One-time Babylonian periods |

| Published in English | AD 1911–2014 |

| Media blazon | Clay tablets |

| Text | Sumerian Rex List at the Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature |

The Sumerian King Listing (abbreviated SKL ) or Chronicle of the One Monarchy is an ancient literary composition written in Sumerian that was likely created and redacted to legitimize the claims to power of diverse city-states and kingdoms in southern Mesopotamia during the late tertiary and early second millennium BC.[two] [iii] [four] It does then by repetitively listing Sumerian cities, the kings that ruled there, and the lengths of their reigns. Especially in the early part of the listing, these reigns oft span thousands of years. In the oldest known version, dated to the Ur III period (c. 2112–2004 BC) simply probably based on Akkadian source material, the SKL reflected a more than linear transition of ability from Kish, the start urban center to receive kingship, to Akkad. In after versions from the Old Babylonian period, the list consisted of a big number of cities betwixt which kingship was transferred, reflecting a more cyclical view of how kingship came to a urban center, only to be inevitably replaced by the adjacent. In its best-known and all-time-preserved version, equally recorded on the Weld-Blundell Prism, the SKL begins with a number of fictional antediluvian kings, who ruled before a flood swept over the land, subsequently which kingship went to Kish. It ends with a dynasty from Isin (early second millennium BC), which is well-known from other contemporary sources.

The SKL is preserved in several versions. Virtually of these appointment to the One-time Babylonian period, but the oldest version dates to the Ur III period. The clay tablets on which the SKL was recorded were generally found on sites in southern Mesopotamia. These versions differ in their exact content; some sections are missing, others are arranged in a dissimilar order, names of kings may be absent or the lengths of their reigns may vary. These differences are both the upshot of copying errors, and of deliberate editorial decisions to change the text to fit electric current needs.

In the by, the Sumerian King List was considered as an invaluable source for the reconstruction of the political history of Early Dynastic Mesopotamia. More contempo research has indicated that the employ of the SKL is fraught with difficulties, and that information technology should only exist used with caution, if at all, in the study of ancient Mesopotamia during the 3rd and early second millennium BC.

Naming conventions [edit]

The text is best known under its modernistic name Sumerian Male monarch Listing, which is often abbreviated to SKL in scholarly literature. A less-used proper noun is the Chronicle of the One Monarchy, reflecting the notion that, according to this text, at that place could e'er be just one city exercising kingship over Mesopotamia.[two] In gimmicky sources, the SKL was called afterward its first word: "nam-lugal", or "kingship".[3] Information technology should also be noted that what is commonly referred to as the Sumerian King List, is in reality not a single text. Rather, it is a literary composition of which different versions existed through fourth dimension in which sections were missing, arranged in a unlike guild, and names, reigns and details on kings were dissimilar or absent.[3]

Modernistic scholarship has used numbered dynasties to refer to the uninterrupted dominion of a single city; hence the Ur Three dynasty denotes the tertiary time that the city of Ur causeless hegemony over Mesopotamia according to the SKL. This numbering (eastward.g. Kish I, Uruk IV, Ur 3) is not present in the original text. It should also be noted that the modern usage of the term dynasty, i.e. a sequence of rulers from a single family, does not necessarily apply to ancient Mesopotamia. Even though the SKL points out that some rulers were family, it was the urban center, rather than individual rulers, to which kingship was given.[two]

Sources [edit]

Map of Republic of iraq showing the archaeological sites where dirt tablets containing (parts of) the Sumerian King List accept been institute.

The Sumerian King List is known from a number of dissimilar sources, all in the form of clay tablets or cylinders and written in Sumerian. At to the lowest degree sixteen unlike tablets or fragments containing parts of the composition are known.[ii] Some tablets are unprovenanced, only most have been recovered, or are known to take come from various sites beyond Mesopotamia, the majority coming from Nippur. So far a version of the SKL has been found outside of Babylonia simply once: there is ane manuscript containing a part of the composition from Tell Leilan in Upper Mesopotamia.[2] [5]

There is only one manuscript that contains a relatively undamaged version of the limerick. This is the Weld-Blundell Prism which includes the antediluvian part of the composition and ends with the Isin dynasty.[6] Other manuscripts are incomplete because they are damaged or fragmentary. The Scheil dynastic tablet, from Susa, for example, only contains parts of the composition running from Uruk II to Ur III.[ii]

The majority of the sources is dated to the Old Babylonian period (early 2d millennium BC), and more specifically the early part of that era. In many cases, a more precise dating is not possible, but one time, the Weld-Blundell prism, it could be dated to year 11 of the reign of king Sin-Magir of Isin, the concluding ruler to be mentioned in the Sumerian King Listing. The and then-called Ur III Sumerian King List (USKL), on a clay tablet peradventure institute in Adab, is the only known version of the SKL that predates the Old Babylonian menses. The colophon of this text mentions that it was copied during the reign of Shulgi (2084–2037 BC), the 2nd king of the Ur III dynasty. The USKL is especially interesting because its pre-Sargonic function is completely dissimilar from that of the SKL. Whereas the SKL records many dissimilar dynasties from several cities, the USKL starts with a single long list of rulers from Kish (including rulers who, in the SKL were function of different Kish dynasties), followed past a few other dynasties, followed again by the kings of Akkad.[2] [iv]

Contents [edit]

Map of Iraq showing the cities that are mentioned in the Sumerian Rex Listing and that have been identified archaeologically. Akkad, Awan, Akshak and Larak take not however been deeply identified. Gutium is located in the Zagros Mountains.

The sources differ in their verbal contents. This is non only the result of many sources being bitty, information technology is as well the result of scribal errors made during copying of the composition, and of the fact that changes were fabricated to the limerick through time. For example, the department on rulers earlier the flood is non present in every copy of the text, including every text from Nippur, where the majority of versions of the SKL was found. Also, the order of some of the dynasties or kings may be changed betwixt copies, some dynasties that were separately mentioned in i version are taken together in another, details on the lengths of individual reigns vary, and individual kings may be left out entirely.[two]

The post-obit summary and line numbers are taken from the compilation past the Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, which in turn takes the text of the Weld-Blundell prism every bit its main source, listing other versions when there are differences in the text.[7] [8]

Lines 1–39: earlier the flood [edit]

This section, which is not nowadays in every copy of the text, opens with the line "After the kingship descended from heaven, the kingship was in Eridu." 2 kings of Eridu are mentioned, before the metropolis "fell" and the "kingship was taken to Bad-tibira". This pattern of cities receiving kingship and then falling or beingness defeated, only to be succeeded by the next, is present throughout the entire text, often in the exact aforementioned words. This start section lists 8 kings who ruled over five cities (apart from Eridu and Bad-tibiru, these besides included Larag, Zimbir and Shuruppag). The duration of each reign is also given. In this start department, the reigns vary between 43,200 and 28,800 years for a full of 241,200 years. The section ends with the line "And then the inundation swept over". Amid the kings mentioned in this department is the ancient Mesopotamian god Dumuzid (the later Tammuz).

Lines 40–265: starting time dynasty of Kish to Lugal-zage-si [edit]

"Afterward the flood had swept over, and the kingship descended from heaven, the kingship was in Kish." After this well-known line, the section goes on to list 23 kings of Kish, who ruled between 1500 and 300 years for a total of 24,510 years. The verbal number of years varies between copies. Autonomously from the lengths of their reigns and whether they were the son of their predecessor (for example, "Mashda, the son of Atab, ruled for 840 years"), no other details are usually given on the exploits of these kings. Exceptions are Etana, "who ascended to heaven and consolidated all the foreign countries" and Enmebaragesi, "who fabricated the land of Elam submit". Enmebaragesi is also the first rex in the Sumerian Male monarch List whose name is attested from contemporaneous (Early on Dynastic I) inscriptions. His successor Aga of Kish, the final male monarch mentioned before Kish fell and kingship was taken to Eastward-ana, also appears in the poem Gilgamesh and Aga.

The next lines, upwards until Sargon of Akkad, evidence a steady succession of cities and kings, usually without much item beyond the lengths of the private reigns. Every entry is structured exactly the same: the city where kingship is located is named, followed by 1 or more kings and how long they reigned, followed by a summary and a final line indicating where kingship went next. Lines 134–147 may serve every bit an example:

In Ur, Mesannepada became rex; he ruled for 80 years. Meskiagnun, the son of Mesannepada, became king; he ruled for 36 years. Elulu ruled for 25 years. Balulu ruled for 36 years. 4 kings; they ruled for 171 years. So Ur was defeated and the kingship was taken to Awan.[7]

Individual reigns vary in length, from 1200 years for Lugalbanda of Uruk, to six years for some other male monarch of Uruk and several kings of Akshak. On average, the number of regnal years decreases downward the listing. Some city names, such as Uruk, Ur and Kish, appear more than than once in the Sumerian King List. The before part of this department mentions several kings who are also known from other literary sources. These kings include Dumuzid the Fisherman and Gilgamesh, although virtually no king from the earlier part of this section appears in inscriptions dating from the actual catamenia in which they were supposed to live. Lines 211–223 describe a dynasty from Mari, which is a city outside Sumer proper simply which played an of import office in Mesopotamian history during the late third and early second millennia BC. The following third dynasty of Kish consists of a unmarried ruler Kug-Bau ("the woman tavern keeper"), thought to be the just queen listed in the Sumerian King Listing. The concluding two dynasties of this section, the quaternary of Kish and the third of Uruk, provide a link to the next section. Sargon of Akkad is mentioned in the Sumerian King Listing as loving cup-bearer to Ur-zababa of Kish, and he defeated Lugal-zage-si of Uruk before founding his own dynasty.

Lines 266–377: Akkad to Isin [edit]

This section is devoted to the well-known Akkadian ruler Sargon and his successors. Afterwards the entry on Shar-kali-sharri, the Sumerian King List reads "Then who was king? Who was not male monarch?", suggesting a period of chaos that may reflect the uncertain times during which the Akkadian Empire came to an end.[9] Four kings are mentioned to take ruled for a full of only 3 years. Of the Akkadian kings mentioned after Shar-kali-sharri, only the names of Dudu and Shu-turul have been attested in inscriptions dating from the Akkadian period. The Akkadian dynasty is succeeded past the fourth dynasty of Uruk, two kings of which, Ur-nigin and his son Ur-gigir, announced in other contemporary inscriptions. Kingship was and then taken to the "state" or "army" of Gutium, of which information technology was said that at outset they had no kings and that they ruled themselves for a few years. After this curt episode, 21 Gutian kings are listed before the fall of Gutium and kingship was taken to Uruk. Simply one ruler is listed during this flow of kingship (Utu-hegal), before it moved on to Ur. The so-called Third Dynasty of Ur consisted of 5 kings who ruled between 9 and 46 years. No other details of their exploits are given. The Sumerian Male monarch Listing remarks that, after the rule of Ur was abolished, "The very foundation of Sumer was torn out", after which kingship was taken to Isin. The kings of Isin are the final dynasty that is included in the list. The dynasty consisted of fourteen kings who ruled between 3 and 33 years. As with the Ur III dynasty, no details are given on the reigns of individual kings.

Lines 378–431: summary [edit]

Some versions of the Sumerian King List conclude with a summary of the dynasties subsequently the alluvion. In this summary, the number of kings and their accumulated regnal years are mentioned for each metropolis, also as the number of times that city had received kingship: "A total of 12 kings ruled for 396 years, 3 times in Urim." The concluding line once again tallies the numbers for all these dynasties: "There are 11 cities, cities in which the kingship was exercised. A total of 134 kings, who altogether ruled for 28876 + X years."

Discussion [edit]

Piotr Steinkeller has observed that, with the exception of the Ballsy of Gilgamesh, in that location might non exist a unmarried cuneiform text with as much "name recognition" equally the Sumerian Rex List. The SKL might also be among the compositions that have fuelled the most intense debate and controversy among academia. These debates by and large focused on when, where and why it was created, and if and how the text tin exist used in the reconstruction of the political history of Mesopotamia during the third and second millennia BC.[iv]

Dating, redaction and purpose [edit]

All only 1 of the surviving versions of the Sumerian King List date to the Old Babylonian catamenia, i.e. the early part of the 2d millennium BC.[10] [9] [xi] One version, the Ur Iii Sumerian King Listing (USKL) dates to the reign of Shulgi (2084–2037 BC). Past advisedly comparing the different versions, peculiarly the USKL with the much later Old Babylonian versions of the SKL, information technology has been shown that the composition that is now known as the SKL was probably kickoff created in the Sargonic period in a course very similar to the USKL. It has even been suggested that this precursor of the SKL was non written in Sumerian, but in Akkadian. The original contents of the USKL, especially the pre-Sargonic function, were probably significantly altered only after the Ur III period, as a reaction to the societal upheaval that resulted from the desintegration of the Ur Iii state at the end of the third millennium BC. This altering of the composition meant that the original long, uninterrupted listing of kings of Kish was cut upward in smaller dynasties (eastward.g. Kish I, Kish II, and then forth), and that other dynasties were inserted. The effect was the SKL as information technology is known from Old Babylonian manuscripts such as the Weld-Blundell prism. The cyclical change of kingship from ane city to the next became a so-chosen Leitmotif, or recurring theme, in the Sumerian King List.[3] [4]

It has been generally accepted that the primary aim was not to provide a historiographical record of the political mural of ancient Mesopotamia.[12] [13] [10] [14] Instead, it has been suggested that the SKL, in its diverse redactions, was used by gimmicky rulers to legitimize their claims to power Babylonia.[two] [3] Steinkeller has argued that the SKL was first created during the Akkad dynasty to position Akkad every bit a directly heir to the hegemony of Kish. Thus, it would make sense to present the predecessors to the Akkadian kings as a long, unbroken line of rulers from Kish. In this way the Akkadian dynasty could legitimize its claims to power over Babylonia by arguing that, from the earliest times onwards, in that location had ever been a single metropolis where kingship was exercised.[4] Later rulers then used the Sumerian Rex List for their own political purposes, amending and adding to the text equally they saw fit. This is why, for instance, the version recorded on the Weld-Blundell prism ends with the Isin dynasty, suggesting that it was at present their turn to rule over Mesopotamia as the rightful inheritors of the Ur 3 legacy.[iii] [13] The use of the SKL as political propaganda may also explain why some versions, including the older USKL, did non contain the antediluvian office of the list. In its original form, the list started with the hegemony of Kish. Some city-states may have been uncomfortable with the preeminent position of Kish. By inserting a section of primordial kings who ruled before a inundation, which is only known from some Old Babylonian versions, the importance of Kish could be downplayed.[3]

Reliability equally a historical source [edit]

During much of the 20th century, many scholars accepted the Sumerian King Listing as a historical source of great importance for the reconstruction of the political history of Mesopotamia, despite the problems associated with the text.[15] [16] [17] For case, many scholars have observed that the kings in the early office of the list reigned for unnaturally long time spans. Various approaches have been offered to reconcile these long reigns with a historical fourth dimension line in which reigns would fall within reasonable human being bounds, and with what is known from the archaeological record as well as other textual sources. Thorkild Jacobsen argued in his major 1939 study of the SKL that, in principle, all rulers mentioned in the listing should be considered historical considering their names were taken from older lists that were kept for authoritative purposes and could therefore be considered reliable. His solution to the reigns considered too long, so, was to fence that "[t]heir occurrence in our material must be ascribed to a tendency known as well amid other peoples of antiquity to form very exaggerated ideas of the length of human life in the earliest times of which they were conscious." In order to create a stock-still chronology where individual kings could be admittedly dated, Jacobsen replaced time spans considered too long with average reigns of twenty–30 years. For instance, Etana ruled for 1500 years co-ordinate to the SKL, just instead Jacobsen assumed a reign of circa 30 years. In this manner, and by working backwards from reigns whose dates could exist independently established by other ways, Jacobsen was able to fit all pre-Sargonic kings in a chronology consistent with the dates that were at that time (1939) accepted for the Early Dynastic period in Mesopotamia.[xv] Jacobsen has been criticised for putting too much faith in the reliability of the king list, for making wishful reconstructions and readings of incomplete parts of the listing, for ignoring inconsistencies between the SKL and other textual evidence, and for ignoring the fact that only very few of the pre-Sargonic rulers have been attested in contemporaneous (i.e. Early on Dynastic) inscriptions.[18]

Others have attempted to reconcile the reigns in the Sumerian King List by arguing that many time spans were really consciously invented, mathematically derived numbers. Rowton, for example, observed that a majority of the reigns in the Gutian dynasty were v, 6, or 7 years in length. In the sexagesimal system used at that time, "nigh 6 years" would be the same as "nearly 10 years" in a decimal system (i.e. a general round number). This was sufficient evidence for him to conclude that at to the lowest degree these figures were completely bogus.[16] The longer time spans from the first office of the listing could also be argued to be artificial: various reigns were multiples of 60 (east.g. Jushur reigned for 600 years, Puannum ruled for 840 years) while others were squares (e.g. Ilku reigned for 900 years (square of thirty) while Meshkiangasher ruled for 324 years (square of 18)).[17]

During the final few decades, scholars have taken a more careful approach. For example, many contempo handbooks on the archaeology and history of ancient Mesopotamia all acknowledge the problematic nature of the SKL and warn that the list's utilise as a historical document for that period is severely limited up to the point that it should not exist used at all.[12] [19] [11] [10] [20] [9] [14] Information technology has been argued, for instance, that the omission of certain cities in the list which were known to have been of import at the time, such every bit Lagash and Larsa, was deliberate.[10] Furthermore, the fact that the SKL adheres to a strict sequential ordering of kingships which were considered equal means that it does no justice at all to the actual complexities of Mesopotamian political history where different reigns overlapped, or where different rulers or cities were not equally powerful.[10] [20] Contempo studies on the SKL even get and so far as to discredit the composition as a valuable historical source on Early Dynastic Mesopotamia birthday. Important arguments to dismiss the SKL every bit a reliable and valuable source are its nature every bit a political, ideological text, its long redactional history, and the fact that out of the many pre-Sargonic kings listed, only 7 take been attested in contemporary Early Dynastic inscriptions.[ii] [3] [18] [four] The final volume on the history and philology of third millennium BC Mesopotamia of the ESF-funded ARCANE-project (Associated Regional Chronologies for the Ancient Near East and the Eastern Mediterranean), for example, did non list any of the pre-Sargonic rulers from the SKL in its chronological tables unless their beingness was corroborated by Early on Dynastic inscriptions.[21]

Thus, in the absence of independent sources from the Early Dynastic period itself, the pre-Sargonic part of the SKL must be considered fictional. Many of the rulers in the pre-Sargonic office (i.eastward. prior to Sargon of Akkad) of the listing must therefore be considered as purely fictional or mythological characters to which reigns of hundreds of years were assigned. All the same, at that place is a small group of pre-Sargonic rulers in the SKL whose names accept been attested in Early on Dynastic inscriptions.This group consists of 7 rulers: Enmebaragesi, Gilgamesh, Mesannepada, Meskiagnun, Elulu, Enshakushanna and Lugal-zage-si.[13] [18] [iii] It has likewise been shown that several kings did not rule sequentially as described past the Sumerian King Listing, but rather contemporaneously.[12] Starting with the Akkadian rulers, but peculiarly for the Ur Three and Isin dynasties, the SKL becomes much more reliable.[11] [ii] Non only are most of the kings attested in other contemporaneous documents, but the reigns attributed to them in the SKL are more or less in line with what can be established from those other sources. This is probably due to the fact that the compilers of the SKL could rely on lists of year names, which came in regular apply during the Akkadian period. Other sources may accept included votive and victory inscriptions.[2] [13]

Nevertheless, while the SKL has little value for the study on Early Dynastic Mesopotamia, it continues to be an important certificate for the report on the Sargonic to Former Babylonian periods. The Sumerian Rex List offers scholars a window into how Old Babylonian kings and scribes viewed their own history, how they perceived the concept of kingship, and how they could have used it to further their own goals. For instance, it has been noted that the king list is unique among Sumerian compositions in there beingness no divine intervention in the procedure of dynastic change.[iii] Also, the style and contents of the Sumerian King List certainly influenced afterwards compositions such as the Curse of Akkad, the Lamentation over Sumer and Akkad, later rex lists such every bit the Assyrian King Listing, and the Babyloniaca by Berossus.[22]

Rulers in the Sumerian King List [edit]

Early dates are approximate, and are based on available archaeological data. For near of the pre-Akkadian rulers listed, the male monarch list is itself the lone source of information. Beginning with Lugal-zage-si and the Third Dynasty of Uruk (which was defeated past Sargon of Akkad), a ameliorate understanding of how subsequent rulers fit into the chronology of the ancient Near East can be deduced. The short chronology is used hither.

Antediluvian rulers

None of the following predynastic antediluvian rulers have been verified as historical by archaeological excavations, epigraphical inscriptions or otherwise. While in that location is no show they ever reigned equally such, the Sumerians purported them to have lived in the mythical era before the cracking deluge.

The "antediluvian" reigns were measured in Sumerian numerical units known as sars (units of three,600), ners (units of 600), and sosses (units of threescore).[23] Attempts have been made to map these numbers into more reasonable regnal lengths.[24]

| Ruler | Epithet | Length of reign | Approx. dates | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Alulim | 8 sars (28,800 years) | Weld-Blundell Prism: initial paragraph almost dominion of Alulim and Alalngar in Eridu for 64.800 years.[25] [26] | |||

| Alalngar | x sars (36,000 years) | ||||

| |||||

| En-men-lu-ana | 12 sars (43,200 years) | ||||

| En-men-gal-ana | viii sars (28,800 years) | ||||

| Dumuzid, the Shepherd | | "the shepherd" | ten sars (36,000 years) | Dumuzid was deified and was the object of later devotional depictions, as the husband of goddess Inanna. | |

| |||||

| En-sipad-zid-ana | 8 sars (28,800 years) | ||||

| |||||

| En-men-dur-ana | 5 sars and 5 ners (21,000 years) | ||||

| |||||

| Ubara-Tutu | 5 sars and 1 ner (eighteen,600 years) | father of Utnapishtim in Epic of Gilgamesh | |||

| |||||

Offset dynasty of Kish

| Ruler | Epithet | Length of reign | Approx. dates | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Jushur | 1,200 years | historicity uncertain | Names before Etana are archaeologically unverified. | ||

| Kullassina-bel | 960 years | ||||

| Nangishlishma | 670 years | ||||

| En-tarah-ana | 420 years | ||||

| Babum | 300 years | ||||

| Puannum | 840 years | ||||

| Kalibum | 960 years | ||||

| Kalumum | 840 years | ||||

| Zuqaqip | 900 years | ||||

| Atab (or A-ba) | 600 years | ||||

| Mashda | "the son of Atab" | 840 years | |||

| Arwium | "the son of Mashda" | 720 years | |||

| Etana | | "the shepherd, who ascended to heaven and consolidated all the foreign countries" | 1,500 years | Myth of Etana exists | |

| Balih | "the son of Etana" | 400 years | |||

| En-me-nuna | 660 years | ||||

| Melem-Kish | "the son of En-me-nuna" | 900 years | |||

| Barsal-nuna | ("the son of En-me-nuna")* | 1,200 years | |||

| Zamug | "the son of Barsal-nuna" | 140 years | |||

| Tizqar | "the son of Zamug" | 305 years | |||

| Ilku | 900 years | ||||

| Iltasadum | 1,200 years | ||||

| Enmebaragesi | | "who made the land of Elam submit" | 900 years | EDI | Primeval ruler on the list to be attested directly from archeology. |

| Aga of Kish |  | "the son of En-me-barage-si" | 625 years | EDI | According to Gilgamesh and Aga he fought Gilgamesh.[xxx] |

| |||||

First rulers of Uruk

| Ruler | Epithet | Length of reign | Approx. dates | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mesh-ki-ang-gasher of E-ana | "the son of Utu" | 324 years | Late Uruk Period | Historicity doubted, thought to be an addition by the Ur Three period.[31] | |

| |||||

| Enmerkar | "the son of Mesh-ki-ang-gasher, the rex of Unug, who congenital Unug (Uruk)" | 420 years | Belatedly Uruk Flow | ||

| Lugalbanda | | "the shepherd" | i,200 years | Late Uruk Period | Historicy is uncertain among scholars.[32] |

| Dumuzid the Fisherman | "the fisherman whose city was Kuara." "He was taken convict by the single hand of Enmebaragesi" | 100 years | Jemdet Nasr menstruation | Historicity doubted, idea to be an addition by the Ur III catamenia.[33] | |

| Gilgamesh | | "whose father was a phantom (?), the lord of Kulaba" | 126 years | EDI | contemporary with Aga of Kish, according to Gilgamesh and Aga[30] |

| Ur-Nungal | "the son of Gilgamesh" | 30 years | |||

| Udul-kalama | "the son of Ur-Nungal" | 15 years | |||

| La-ba'shum | ix years | ||||

| En-nun-tarah-ana | 8 years | ||||

| Mesh-he | "the smith" | 36 years | |||

| Melem-ana | half dozen years | ||||

| Lugal-kitun | 36 years | ||||

| |||||

Showtime dynasty of Ur

| Ruler | Epithet | Length of reign | Approx. dates | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mesh-Ane-pada | | 80 years | c. 27th century BC | Existence is likely equally it is supported by lot of tablets. | |

| Mesh-ki-ang-Nuna | | "the son of Mesh-One-pada" | 36 years | ||

| Elulu | | 25 years | |||

| Balulu | 36 years | ||||

| |||||

Dynasty of Awan

This was a dynasty from Elam.

| Ruler | Epithet | Length of reign | Approx. dates | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Three kings of Awan | 356 years | |||

| ||||

Second dynasty of Kish

| Ruler | Epithet | Length of reign | Approx. dates | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Susuda | "the fuller" | 201 years | EDII | |

| Dadasig | 81 years | |||

| Mamagal | "the boatman" | 360 years | ||

| Kalbum | "the son of Mamagal" | 195 years | ||

| Tuge | 360 years | |||

| Men-nuna | "the son of Tuge" | 180 years | ||

| (Enbi-Ishtar) | 290 years | |||

| Lugalngu | 360 years | |||

| ||||

The First dynasty of Lagash (c. 2500 – c. 2271 BC) is not mentioned in the King List, though information technology is well known from inscriptions

Dynasty of Hamazi

| Ruler | Epithet | Length of reign | Approx. dates | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hadanish | 360 years | |||

| ||||

Second dynasty of Uruk

| Ruler | Epithet | Length of reign | Approx. dates | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| En-shag-kush-ana | | 60 years | c. 25th century BC | said to have conquered parts of Sumer; then Eannatum of Lagash claims to have taken over Sumer, Kish, and all Mesopotamia. | |

| Lugal-kinishe-dudu or Lugal-ure | | 120 years | contemporary with Entemena of Lagash | ||

| Argandea | 7 years | ||||

| |||||

2nd dynasty of Ur

| Ruler | Epithet | Length of reign | Approx. dates | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nanni | 120 years | |||

| Mesh-ki-ang-Nanna 2 | "the son of Nanni" | 48 years | ||

| ||||

Dynasty of Adab

Other rulers of Adab are known, also Lugal-Ane-mundu, only they are not mentioned in the Sumerian Rex List.

| Ruler | Epithet | Length of reign | Approx. dates | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lugal-Ane-mundu | | xc years | c. 25th century BC | Known from other inscriptions. Said to have conquered all Mesopotamia from the Persian Gulf to the Zagros Mountains and Elam.[34] [35] | |

| |||||

Dynasty of Mari

Many rulers are known from Mari, but different names are mentioned in the Sumerian male monarch list.

| Ruler | Epithet | Length of reign | Approx. dates | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anbu | 30 years | |||

| Anba | "the son of Anbu" | 17 years | ||

| Bazi | "the leatherworker" | 30 years | ||

| Zizi of Mari | "the fuller" | 20 years | ||

| Limer | "the 'gudug' priest" | 30 years | ||

| Sharrum-iter | 9 years | |||

| ||||

Third dynasty of Kish

| Ruler | Epithet | Length of reign | Approx. dates | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kug-Bau (Kubaba) | "the woman tavern-keeper, who fabricated business firm the foundations of Kish" | 100 years | c. 24th century BC | the simply known woman in the King List; said to have gained independence from En-anna-stomach I of Lagash and En-shag-kush-ana of Uruk; contemporary with Puzur-Nirah of Akshak, co-ordinate to the afterward Chronicle of the É-sagila |

| ||||

Dynasty of Akshak

| Ruler | Epithet | Length of reign | Approx. dates | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unzi | thirty years | |||

| Undalulu | 6 years | |||

| Urur | 6 years | |||

| Puzur-Nirah | xx years | contemporary with Kug-Bau of Kish, according to the afterwards Chronicle of É-sagila | ||

| Ishu-Il | 24 years | |||

| Shu-Suen of Akshak | "the son of Ishu-Il" | 7 years | ||

| ||||

4th dynasty of Kish

| Ruler | Epithet | Length of reign | Approx. dates | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Puzur-Suen | "the son of Kug-Bau" | 25 years | c. 2350 BC | |

| Ur-Zababa | "the son of Puzur-Suen" | 400 (6?) years | c. 2350 BC | according to the king listing, Sargon of Akkad was his cup-bearer |

| Zimudar | 30 years | |||

| Usi-watar | "the son of Zimudar" | vii years | ||

| Eshtar-muti | eleven years | |||

| Ishme-Shamash | 11 years | |||

| (Shu-ilishu)* | (15 years)* | |||

| Nanniya | "the jeweller" | 7 years | ||

| ||||

Third dynasty of Uruk

| Ruler | Epithet | Length of reign | Approx. dates | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lugal-zage-si | | 25 years | c. 2296–2271 BC (short) | said to take defeated Urukagina of Lagash, as well as Kish and other Sumerian cities, creating a unified kingdom; he in plow was overthrown by Sargon of Akkad | |

| |||||

Dynasty of Akkad

| Ruler | Epithet | Length of reign | Approx. dates | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sargon of Akkad | | "whose father was a gardener, the cupbearer of Ur-Zababa, became king, the king of Agade, who built Agade" | 40 years | c. 2270–2215 BC (brusk) | Defeated Lugal-zage-si of Uruk, took over Sumer, and began the Akkadian Empire |

| Rimush of Akkad | | "the son of Sargon" | ix years | c. 2214–2206 BC (brusk) | |

| Manishtushu | | "the older blood brother of Rimush, the son of Sargon" | 15 years | c. 2205–2191 BC (short) | |

| Naram-Sin of Akkad | | "the son of Man-ishtishu" | 56 years | c. 2190–2154 BC (short) | |

| Shar-kali-sharri | | "the son of Naram-Sin" | 25 years | c. 2153–2129 BC (short) | |

| |||||

| four years | c. 2128–2125 BC (short) | |||

| Dudu of Akkad | | 21 years | c. 2125–2104 BC (curt) | ||

| Shu-Durul | | "the son of Dudu" | 15 years | c. 2104–2083 BC (short) | Akkad falls to the Gutians |

| |||||

Quaternary dynasty of Uruk

-

- (Possibly rulers of lower Mesopotamia contemporary with the Dynasty of Akkad)[ commendation needed ]

| Ruler | Epithet | Length of reign | Approx. dates | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ur-ningin | vii years | c. 2091? – 2061? BC (brusk) | Known from inscriptions.[36] | |

| Ur-gigir | "the son of Ur-ningin" | 6 years | Known from inscriptions.[36] | |

| Kuda | vi years | |||

| Puzur-ili | 5 years | |||

| Ur-Utu (or Lugal-melem) | ("the son of Ur-gigir")* | 25 years | ||

| ||||

The 2d dynasty of Lagash (earlier c. 2093–2046 BC (brusque)) is non mentioned in the King List, though it is well known from inscriptions.

Gutian rule

| Ruler | Length of reign | Approx. dates | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Inkišuš | 6 years | c. 2147–2050 BC (short) | Mention of the Gutian dynasty of Sumer in the tablet of Lugalanatum (𒄖𒋾𒌝𒆠, gu-ti-umKI) | |

| Sarlagab (or Zarlagab) | 6 years | |||

| Shulme (or Yarlagash) | 6 years | |||

| Elulmeš (or Silulumeš or Silulu) | vi years | |||

| Inimabakeš (or Duga) | 5 years | |||

| Igešauš (or Ilu-An) | 6 years | |||

| Yarlagab | 3 years | |||

| Ibate of Gutium | three years | |||

| Yarla (or Yarlangab) | 3 years | |||

| Kurum | 1 year | |||

| Apilkin | 3 years | |||

| La-erabum | | ii years | mace caput inscription | |

| Irarum | two years | |||

| Ibranum | 1 twelvemonth | |||

| Hablum | 2 years | |||

| Puzur-Suen | 7 years | "the son of Hablum" | ||

| Yarlaganda | 7 years | foundation inscription at Umma | ||

| Unknown | | vii years | Si'um or Si-u? — foundation inscription at Umma | |

| Tirigan | 40 days | defeated by Utu-hengal of Uruk | ||

| ||||

5th dynasty of Uruk

| Ruler | Epithet | Length of reign | Approx. dates | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Utu-hengal | | conflicting dates (427 years / 26 years / seven years) | c. 2055–2048 BC (short) | defeats Tirigan and the Gutians, appoints Ur-Namma governor of Ur |

3rd dynasty of Ur

| Ruler | Epithet | Length of reign | Approx. dates | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ur-Namma (Ur-Nammu) | | "the son of Utu-Hengal" | eighteen years | c. 2047–2030 BC (short) | defeats Nammahani of Lagash; contemporary of Utu-hengal of Uruk |

| Shulgi | | "the son of Ur-Namma" | 46 years | c. 2029–1982 BC (short) | possible lunar/solar eclipse 2005 BC |

| Amar-Suena | | "the son of Shulgi" | 9 years | c. 1981–1973 BC (short) | |

| Shu-Suen | | "the son of Amar-Suena" | 9 years | c. 1972–1964 BC (short) | |

| Ibbi-Suen | | "the son of Shu-Suen" | 24 years | c. 1963–1940 BC (short) | |

| |||||

Dynasty of Isin

Independent Amorite states in lower Mesopotamia. The Dynasty of Larsa (c. 1961–1674 BC (short)) from this menstruum is not mentioned in the King List.

| Ruler | Epithet | Length of reign | Approx. dates | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ishbi-Erra | 33 years | c. 1953–1920 BC (curt) | contemporary of Ibbi-Suen of Ur | ||

| Shu-Ilishu | "the son of Ishbi-Erra" | xx years | |||

| Iddin-Dagan | | "the son of Shu-ilishu" | 20 years | ||

| Ishme-Dagan | | "the son of Iddin-Dagan" | 20 years | ||

| Lipit-Eshtar | | "the son of Ishme-Dagan (or Iddin-Dagan)" | 11 years | contemporary of Gungunum of Larsa | |

| Ur-Ninurta | ("the son of Ishkur, may he accept years of affluence, a skilful reign, and a sweet life")* | 28 years | Contemporary of Abisare of Larsa | ||

| Bur-Suen | | "the son of Ur-Ninurta" | 21 years | ||

| Lipit-Enlil | "the son of Bur-Suen" | 5 years | |||

| Erra-imitti | 8 years | He appointed his gardener, Enlil-Bani, substitute rex and and then suddenly died. | |||

| Enlil-bani | | 24 years | contemporary of Sumu-la-El of Babylon. He was Erra-imitti's gardener and was appointed substitute king, to serve as a scapegoat and then sacrificed, but remained on the throne when Erra-imitti suddenly died. | ||

| Zambiya | | 3 years | contemporary of Sin-Iqisham of Larsa | ||

| Iter-pisha | 4 years | ||||

| Ur-du-kuga | 4 years | ||||

| Suen-magir | xi years | ||||

| (Damiq-ilishu)* | | ("the son of Suen-magir")* | (23 years)* |

* These epithets or names are not included in all versions of the rex list.

Come across also [edit]

- Chronology of the aboriginal Near East

- History of Sumer

- List of Mesopotamian dynasties

References [edit]

- ^ Mesopotamia: The Earth's Primeval Civilization. Britannica Educational Publishing. 1 Apr 2010. p. 45. ISBN978-1-61530-208-6.

- ^ a b c d eastward f g h i j g l grand Sallaberger, Walther; Schrakamp, Ingo (2015). "Part I: Philological data for a historical chronology of Mesopotamia in the 3rd millennium". History & philology. Turnhout. pp. 1–133. ISBN978-2-503-53494-7. OCLC 904661061.

- ^ a b c d east f g h i j Marchesi, Gianni (2010). "The Sumerian Rex List and the Early History of Mesopotamia". M. G. Biga - M. Liverani (eds.), ana turri gimilli: Studi dedicati al Padre Werner R. Mayer, S. J., da amici e allievi (Vicino Oriente - Quaderno 5; Roma): 231–248.

- ^ a b c d due east f Steinkeller, Piotr (2003). "An Ur III Manuscript of the Sumerian King List". Literatur, Politik und Recht in Mesopotamien: Festschrift fur Claus Wilcke: 267–292.

- ^ Vincente, Claudine-Adrienne (1995-01-01). "The Tall Leilãn Recension of the Sumerian King List" (in German). 85 (2): 234–270. doi:x.1515/zava.1995.85.two.234. ISSN 1613-1150.

- ^ "SUMERIAN King LIST". www.ashmolean.org . Retrieved 2021-06-29 .

- ^ a b "The Sumerian king list: translation". etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk . Retrieved 2021-06-30 .

- ^ Friberg, Jöran (2007). A remarkable collection of Babylonian mathematical texts. New York: Springer. ISBN978-0-387-48977-3. OCLC 191464830.

- ^ a b c Roaf, Michael (1990). Cultural atlas of Mesopotamia and the ancient Near East. New York, NY. ISBN0-8160-2218-vi. OCLC 21523764.

- ^ a b c d e Postgate, J. N. (1992). Early Mesopotamia : society and economic system at the dawn of history. London: Routledge. ISBN0-415-00843-three. OCLC 24468109.

- ^ a b c Crawford, Harriet E. Due west. (1991). Sumer and the Sumerians. Cambridge: Cambridge Academy Press. ISBN0-521-38175-4. OCLC 20826485.

- ^ a b c Van De Mieroop, Marc (2004). A History of the Ancient Near East. Blackwell. ISBN0-631-22552-8.

- ^ a b c d Michalowski, Piotr (1983). "History every bit Charter Some Observations on the Sumerian King Listing". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 103 (1): 237–248. doi:x.2307/601880. ISSN 0003-0279.

- ^ a b Pollock, Susan (1999). Ancient Mesopotamia : the eden that never was. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN0-521-57334-3. OCLC 40609053.

- ^ a b Jacobsen, Thorkild (1939). The Sumerian king list. Chicago (Ill.): the University of Chicago press. ISBN0-226-62273-eight. OCLC 491884743.

- ^ a b Rowton, M. B. (1960-04-01). "The Date of the Sumerian King List". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 19 (2): 156–162. doi:10.1086/371575. ISSN 0022-2968.

- ^ a b Immature, Dwight Due west. (1988). "A Mathematical Approach to Certain Dynastic Spans in the Sumerian King List". Journal of Almost Eastern Studies. 47 (2): 123–129. ISSN 0022-2968.

- ^ a b c "ANE TODAY - 201611 - The Sumerian King List or the 'History' of Kingship in Early Mesopotamia". American Lodge of Overseas Research (ASOR) . Retrieved 2021-06-29 .

- ^ von Soden, Wolfram (1994). The Ancient Orient . Donald G. Schley (trans.). Wm. B. Eerdmans. pp. 47. ISBN0-8028-0142-0.

- ^ a b Nissen, Hans Jörg (1988). The early history of the aboriginal Near Due east, 9000-2000 B.C. Elizabeth Lutzeier, Kenneth J. Northcott. Chicago. ISBN978-0-226-18269-viii. OCLC 899007792.

- ^ Marchesi, Gianni. "Toward a Chronology of Early Dynastic Rulers in Mesopotamia". in W. Sallaberger and I. Schrakamp (eds.), History & Philology (ARCANE 3; Turnhout), pp. 139-156.

- ^ "The Sumerian King List (SKL) [CDLI Wiki]". cdli.ox.air conditioning.uk . Retrieved 2021-07-03 .

- ^ "Archived re-create". Archived from the original on 2012-01-xxx. Retrieved 2011-03-ten .

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as championship (link) Christine Proust, "Numerical and Metrological Graphemes: From Cuneiform to Transliteration," Cuneiform Digital Library Journal, 2009, ISSN 1540-8779 - ^ R.Grand. Harrison, "Reinvestigating the Antediluvian Sumerian Rex List," JETS, vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 3-8, (Mar 1993)

- ^ Langdon, S. (1923). The Weld-Blundell Collection, vol. II. Historical Inscriptions, Containing Principally the Chronological Prism, W-B. 444 (PDF). OXFORD EDITIONS OF CUNEIFORM TEXTS. pp. eight–21.

- ^ Milstein, Sara Jessica (2016). Tracking the Master Scribe: Revision Through Introduction in Biblical and Mesopotamian Literature. Oxford Academy Press. p. 45. ISBN978-0-19-020539-3.

- ^ a b c d eastward f yard h i j one thousand l m north o p q r south t "The Sumerian king list: translation". etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 2008-05-08.

- ^ a b c d e f one thousand h i j thou l yard northward o p q r s t Langdon, Stephen Herbert (1923). Oxford editions of cuneiform texts (PDF). Oxford University Printing. pp. one–27, Plates I-IV.

- ^ a b c d e f chiliad h i j k l thou n o p q r due south t "CDLI-Archival View". cdli.ucla.edu.

- ^ a b [1] Archived 2016-x-09 at the Wayback Car Gilgameš and Aga Translation at ETCSL

- ^ Drewnowska, Olga; Sandowicz, Malgorata (2017). Fortune and Misfortune in the Ancient Near East. Winona Lake, Indiana: EISENBRAUNS. p. 201.

- ^ Lugalbanda, Reallexikon der Assyriologie seven, p. 117.

- ^ Mittermayer, Catherine (2009). Enmerkara und der Herr von Arata: Ein ungleicher Wettstreit. p. 93.

- ^ "Lugal-Anne-Mundu inscription CDLI-Found Texts". cdli.ucla.edu.

- ^ "The Names of the Leaders and Diplomats of Marḫaši and Related Men in the Ur Iii Dynasty". cdli.ucla.edu.

- ^ a b "CDLI-Found Texts". cdli.ucla.edu.

Further reading [edit]

- Albright, Westward. F. (1923). "The Babylonian Antediluvian Kings". Journal of the American Oriental Social club. 43: 323–329. doi:10.2307/593359. ISSN 0003-0279.

- Glassner, Jean-Jacques (2004). Mesopotamian chronicles. Benjamin R. Foster. Atlanta: Club of Biblical Literature. ISBN90-04-13084-5. OCLC 558440503.

- Goetze, Albrecht (1961-06-01). "Early on Kings of Kish". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 15 (3): 105–111. doi:10.2307/1359020. ISSN 0022-0256.

- Hallo, William W. (1963-03-01). "Outset and End of the Sumerian King List in the Nippur Recension". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 17 (2): 52–57. doi:10.2307/1359064. ISSN 0022-0256.

- Young, Dwight W. (1991). "The Incredible Regnal Spans of Kish I in the Sumerian Male monarch List". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 50 (1): 23–35. ISSN 0022-2968.

External links [edit]

- Full translation of the SKL at The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature

- Full translation of the SKL at Livius.org

- Bibliography on the Sumerian King List

- Composite list of SKL sources and images at CDLI

depasqualedoperelpland.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sumerian_King_List

0 Response to "How Do Rulers Use Art and Architecture to Legitimize Their Rule"

Post a Comment